This essay was written by Aaron Vanek, one of the contributing authors and major playtesters of Dreamland: Fairytale Portal Fantasy Beyond the Wall of Sleep. We’re honored & flattered to post it here in two parts.

By Aaron Vanek

Artist Jason Bradley Thompson, whose orbit transited mine when I hired him to create a wonderful poster for the 2013 H.P. Lovecraft Film Festival Los Angeles, has spent years developing a tabletop role-playing game called Dreamland. I first heard about it from his Facebook post in late 2020. My interest was roused because of the setting and the interesting mechanic of speaking and using words, which I thought could be a good tack toward vocabulary building in game-based learning, a pedagogy that I utilize.

I requested a playtest copy and rapidly became enraptured by the game. Some months later, Jason asked if I would be interested in doing some worldbuilding for it.

YES!

Since then, I have run roughly two dozen Dreamland one-shots at various conventions, game stores and online, plus wrote and ran a campaign that lasted over 100 hours.

I’ve witnessed the many tweaks and iterations that Jason made along the way, oftentimes with my input, sometimes with my suggestions. I am excited about the future of Dreamland, and I am going to detail below the reasons why I enjoy the game so much.

If it wasn’t obvious, I am quite biased toward Dreamland—I was paid to write for the game, but not to write this essay. Tellingly, I was a fan of the game first, arriving at the right moment in its blooming to be able to help cultivate.

I hope you look at the enumeration below as an insider’s perspective. You might like other things about the game once you have been experienced, and there might be things you don’t like, or the qualities I detail below happen to be facets you don’t like in ttRPGs. Are there other games that have these traits? Assuredly. Do the others deploy them better than Dreamland? Possibly. However, these are some of my buttons for ttRPG enjoyment, and Dreamland mashes them all. Your jollity may vary.

1. The Setting

Jason leaned heavily into the works of Edward John Moreton Drax Plunkett, a.k.a. Lord Dunsany (1878-1957). I had heard of Dunsany’s influence on H.P. Lovecraft, but alas, had not read his words until I needed to research them for my contributions to the game. Gadzooks! I greatly enjoy the Baron’s oeuvre, and many other fantasists like Lovecraft, Robert Howard, J.R.R. Tolkien, Jorge Luis Borges, Ursula Le Guin, Peter Beagle, Neil Gaiman, et al., concur. Although I wouldn’t classify Dunsany’s short stories, novels, poems or plays as horror (though some could be regarded as such), there is a bittersweet melancholy to most of them that suits my middle-aged demeanor like cotton sweatpants and after-dinner naps. Recurrent themes in Dunsany are mortality, pastoral nostalgia, and divine whimsy.

Many of Dunsany’s works take place in a twilight fantasy universe that he created (see The Gods of Pegāna). In some tales the country is accessible through dreaming. Jason used much of this mythology for Dreamland, and it feels like he rediscovered one of the original IPs, now largely in the public domain.

Jason grafted other writers and styles to this Dunsany sprout: Lovecraft, Michael Ende (The Neverending Story), Kij Johnson (author of the award-winning The Dream-Quest of Vellitt Boe), isekai anime, and travelogues such as Invisible Cities by Italo Calvino. And they all entwine, since their roots reach to Dunsany.

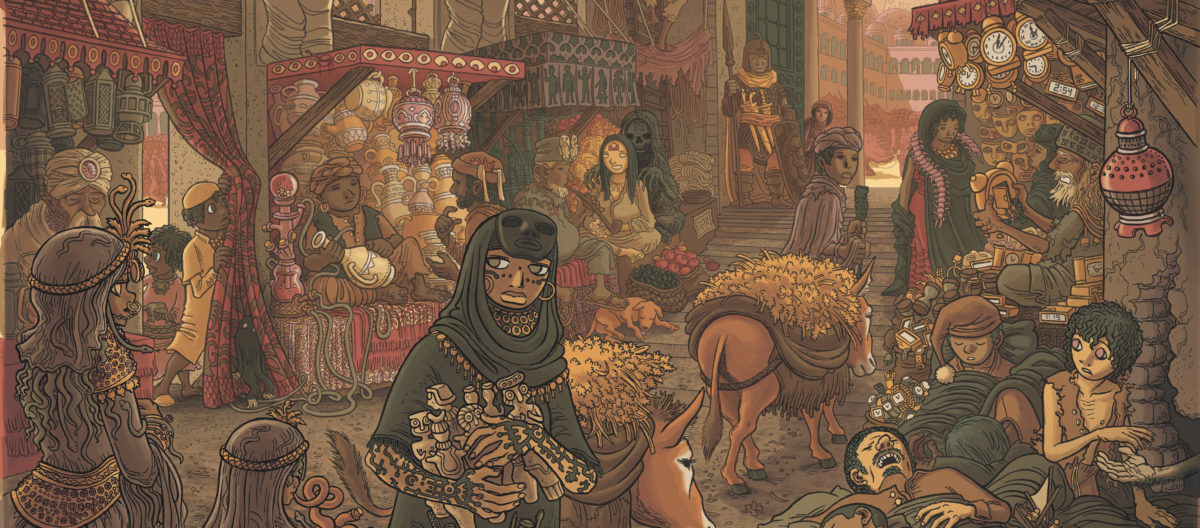

Besides applying the mapped and measured realms dreamt by the above authors, I especially appreciate that Jason left Dreamland both open and expanding. When I was under deadline to produce content, I felt intimidated trying to accompany masters Dunsany, Lovecraft, Johnson, and others. In some instances, I had to translate their prose into RPG fodder. But I eventually noticed a lacuna to exploit: conventional dreams and night terrors were largely absent. This inspired many of my entries, especially a section called The Mapless Lands.

Jason unlatched the geographic borders inside the game. He pays less intention to the proximity of Bethmoora (from Dunsany) to Dylath-Leen (from Lovecraft) than the impetus to accept all fantastical zones conceived by people, published or not. I can run a Dreamland adventure in an Underworld populated by ghouls, gugs, and ghasts harrying the trekking Orpheus and Eurydice while they flee my imagination’s own peculiar Stygian torments—and yours can stalk alongside, too.

2. Game Style

I relish Dreamland like a Goldilocks’ porridge for gamers: not too traditional, not too indie. In the traditional sense, there is still a single Game Master (Dream Master, the DM) who narrates everything except the actions of the player characters and who portrays the antagonists in a pre-scripted plot—though there’s enough material to improvise an adventure from the random tables and gazetteer entries if you’re partial to DMing by the seat of your pants. I prefer this setup instead of the indie RPG trope expecting players to function as GMs and create content on the fly.

However, during Waking World scenes, when the player plays her dream role’s alter ego in the “real” world, the player has full narrative sway over their character—with exceptions if dreams intrude. The majority of playtime is spent in dream, but the freedom of players to control what happens to their character after they wake up stimulates my creative side, especially the ability to manufacture new memories that benefit the character’s Dreamer half. Other players can act as NPCs and suggest ideas during these scenes, but the lead player has the final word about their waking character. Again, there are exceptions, mainly the Dream Shock Impairments.

For me, a roughly 90% traditional RPG with 10% indie aspects (GM-less/GM-full) strikes the right balance between the two styles.

3. Marvels by Memories

In Dreamland, each character has three Memories that operate like three legs of a table supporting their persona. Memories might be of their childhood home, a loved one, a job, a traumatic experience, etc. Sacrificing and forgetting these Memories actuate the dreaming character to create Marvels, e.g., controlling the weather, constructing treasures, summoning creatures or even friendly NPCs. (Forgetting memories for effect is featured in The Neverending Story, the original novel.)

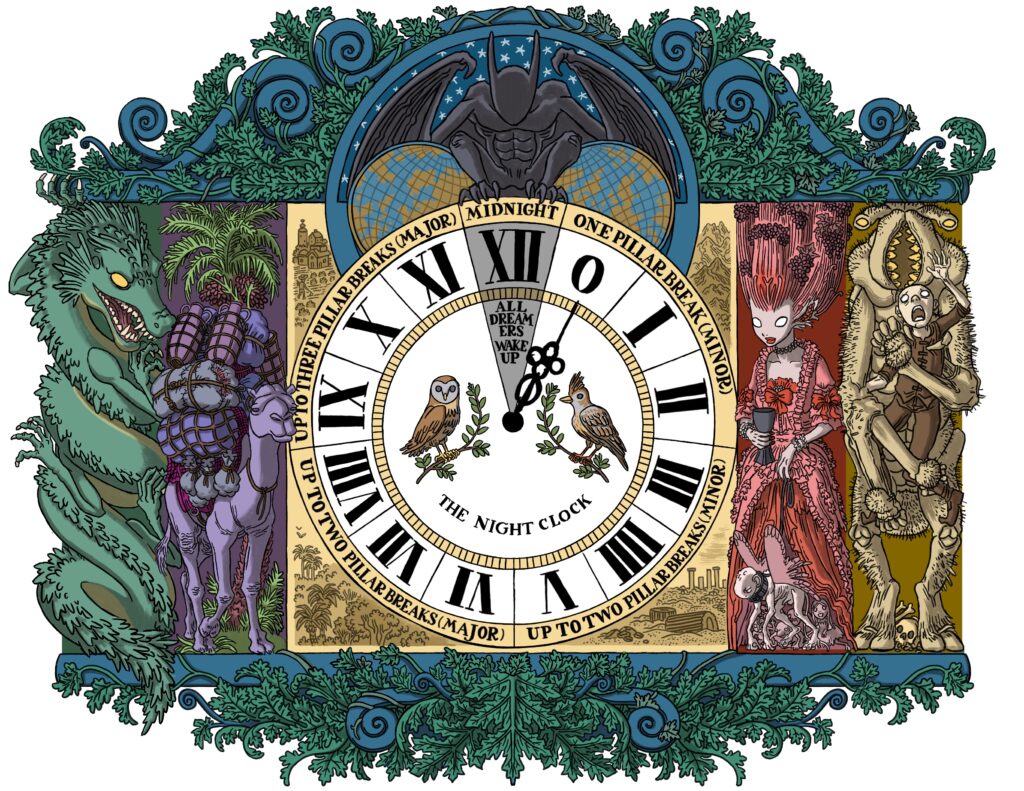

Like the trad/indie balance, Memories also sit in my Goldilocks zone: a player can detail any Memory they want as director of their character’s waking life and attach it to any of the Five Pillars*, then during dreamtime spend it to generate something useful—a Marvel. But the Marvel possibilities are corralled by the type of Pillar the Memory is, for dreamers can’t do just anything. For example, by sacrificing part of a Wonder Memory, a Dreamer can create a small treasure or a beast, but the fauna will be one that is relatively common, like a cat, dog, camel, etc., and only one appears unless Words are spent as a force multiplier; more opinion on the Word mechanic is below. Abandoning a Mystery Memory allows a character to perceive invisible things or fabricate a handheld tool or device, but what that object does is up to the PC.

This bounded creativity for making Memories and using them—creating any kind of animal as long as it’s ordinary and only one or conveniently finding in their purse any non-magical handheld device the character could envision—rests happily within my mental factory.

(* There are Five Pillars, five concepts that define and brace Dreamland. They are Wonder, Mystery, Passion, Loathing, and Faraway.)

4. The Word Mechanic

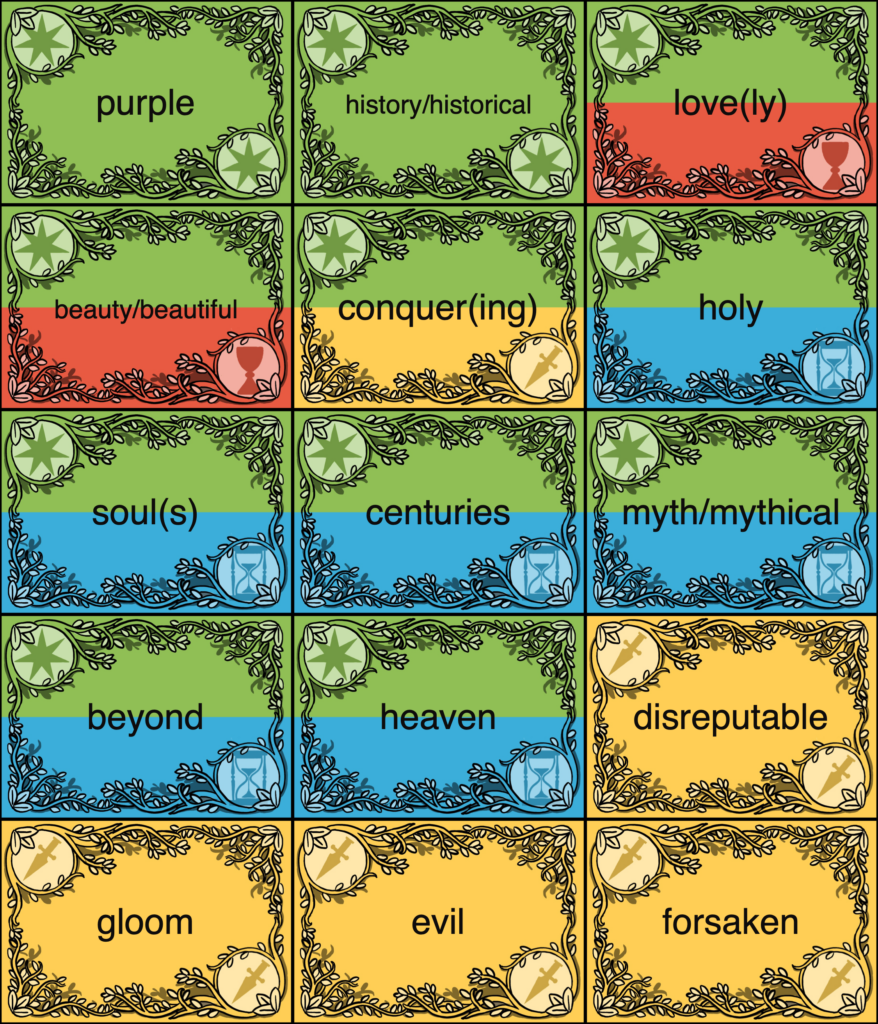

A unique feature of Dreamland (I am ignorant of any other RPGs that do this) involves a pool of random words on matching Pillar-colored cards placed on the table. Words can be used to add a bonus to a skill roll, boost a Marvel, activate role-specific abilities, and most other character actions; it’s the game’s core loop.

To use Words, the player speaks in character or about their character using selected words from the pool.

Besides broadening one’s personal lexicon, I really enjoy Dreamland’s literary mechanic over most ttRPG’s numerary ones. Using evocative words to perform character moves keeps players focused on the diction of the fiction. Plus, words provide a trellis to support role-playing. One of the finer one-shots I ran featured a lyricist-by-trade player who created poems with their Words and then sang as their character! But possible players, never fear, it doesn’t matter what you say or how well you articulate it. I also see potential in non-English versions of the Word Deck in Dreamland.

(Jason selected the words for the game from Lord Dunsany’s corpus, but another famous author’s “tentacular” prose could become a second set.)

5. 1D6 Rolls

Besides the Word mechanic, I also appreciate that challenges within Dreamland are typically settled quickly, with one 1d6 roll each between a PC and the DM. Combat is not granular—there’s no maneuvering 10 feet for a backstab bonus, no programming a free action to dive for cover after striking, etc. Entire battles rarely require more than a few minutes to resolve.

Disclosure: I have nothing against those who count hexes and compare range mods. I have done so in the past and expect to do so in the future, but it’s not my preferred feature for most TTRPGs.

To Be Continued…!

One thought on “Things I Like About Dreamland, Part 1”