Since language is such an important thing in the mood of Lovecraft and Dunsany fantasy stories, and fairytales in general, my goal when I started working on Dreamland was “a game whose core component is language”.

A quick google search early on showed that there weren’t many tabletop games whose rules affected how players could speak to one another: (1) “Ugg-Tect” in tabletop games, (2) “Land of Og” in RPGs, and (3) Robin Laws’ brilliant “The Dying Earth” RPG, which has a bit of this in the way in which players are incentived to use catchphrases from Jack Vance’s stories. (All 3 of these games are awesome, BTW.)

My initial Dreamland idea was for a very simple game where players were rewarded for doing two conflicting things:

(1) using ‘fantasy words’ (the colorful, flowery language of Dunsany and fairytales), that link characters to the ‘fantasy world’

(2) remembering simple ‘normal phrases’ that link characters to the ‘real world’

The second part, memorization, was tricky and I didn’t go far in that direction. (Though it’s fun to memorize your lines in high school drama class, rewarding real-world memorization skills in a RPG subtracts more than it adds.) The ‘fantasy words’ part was more promising…but what should the ‘fantasy words’ be? As an experiment, I used online word-cloud software, of the type that Ruth Tillman used to sort out the most common words used by HP Lovecraft. I fed it the entire text of Dunsany’s early out-of-copyright short story collections, the software sorted the words by length and frequency and, after I removed the “of”s and “and”s and boring verbs and plurals and repetitions, I got a long list of words like:

night

city

little

sea

old

captain

world

river

evening

king

soul(s)

wind

cities

song

dark

Going down the list was a bit like those articles of “how much can you say with just 300 words in a foreign language?” It sounds silly, listing them off like a grocery list, but buried beneath the silliness is a kind of beauty. You could do the same with Lovecraft’s writing, or Clark Ashton Smith’s, or any writer, but Dunsany’s writing offered the richest mix, the most evocative adjectives, the most vivid images. (Dunsany really is a better writer than Lovecraft, on a pure prose level.) I broke Dunsany’s stories down into building-blocks of words, reconstituted from word-atoms, gamified with word-meeples.

But how to represent Words at the table? My first attempt resulted in 205 tokens which I cut out, laminated, and cut out again to make laminated Word Tokens:

Players immediately told me that these tokens were super small and hard to read. (Notice the numbers in parentheses on the Words? Another rejected rule…) I increased the size repeatedly, as well as increasing the number of Words from 205 to 240.

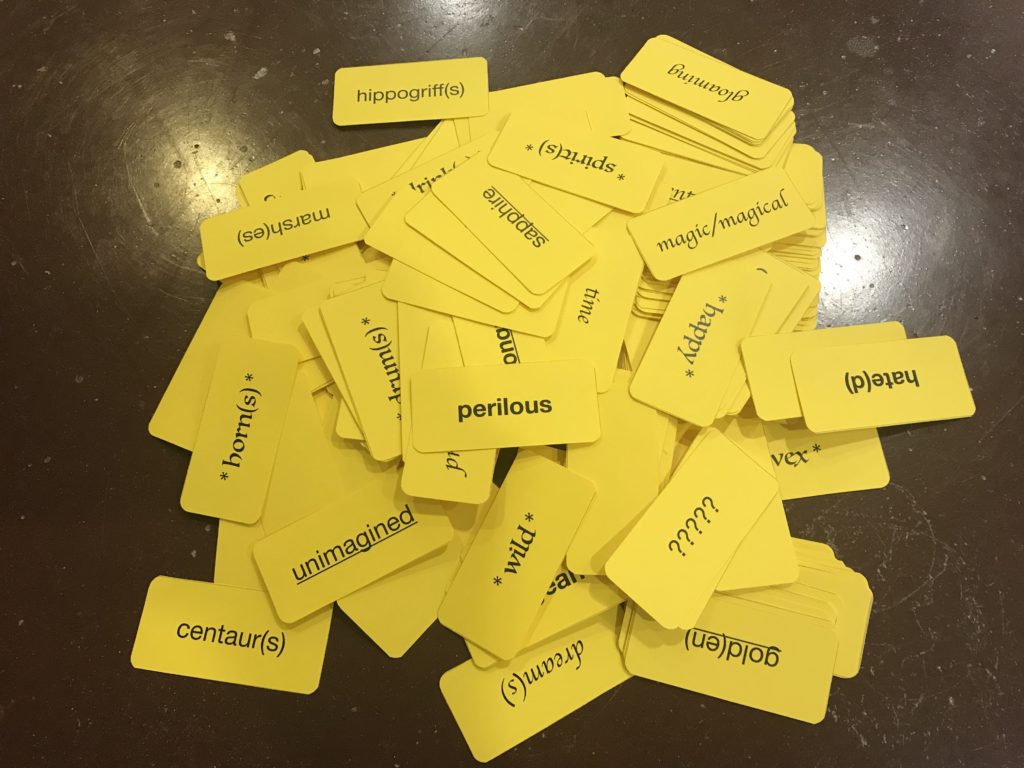

Eventually I discovered that lamination was more trouble than it’s worth, and that plain cardstock Words are just as easy to manipulate at the table (bevelling the edges helps):

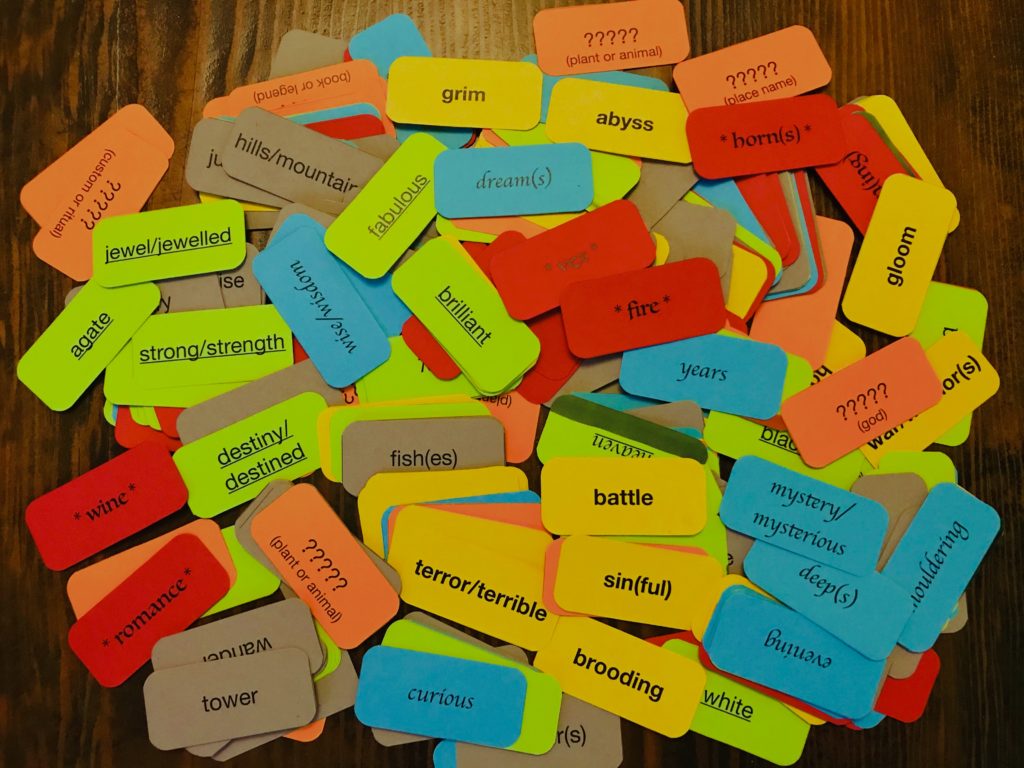

And finally, I went with something important: color-coding to distinguish between the different types of Words! (Because once I sifted Dunsany’s writing, it became evident there were pretty clear categories for his most commonly used types of words.) These colors were just whatever colored cardstock I could grab at Office Depot, not final colors optimized for viewing by the colorblind, but the color-coding was a huge help at the table.

By this point the number of Words had increased to 300, and the Words had been divided into their final categories. But how to use them in the game? That’ll be in the next post.