Dreamland is infinite, and one of the things I wanted to do in Dreamland RPG was have a world which doesn’t depend on “canon” or on a small important landmass where everyone lives and everything happens. Almost anything can exist in Dreamland, and the intention is that DMs and players can create different types of places and stories within Dreamland. Dreamland is too big to be fully explored, too big to be saved, too big to be comprehended.

That said, the game makes certain assumptions which are worked into the game system:

- a predominantly Bronze Age or Medieval fantasy setting

- use of fantasy archetypes (dragons, knights, monsters, treasure, etc.)

- use of character archetypes (Roles)

- use of eloquent and ornate language

- use of travel as a challenge, and as a metaphor for a spiritual journey

- …and of course, the idea that the adventurers are *dreamers*; they’re outsiders who aren’t from this place, at least not completely so. Being a dreamer is what gives them the power to be heroes and wonder-workers (or tyrants and exploiters) in Dreamland.

To break it down to a few words, by default, Dreamland is a wondrous, sometimes scary, sometimes heavy game, set in a low-tech, exotic fantasy world, in which the players are isolated adventurers.

And now, to indulgently expand those few words out to a few thousand words, here’s a little more about what that means, and how different DMs/groups can fiddle with these dials to produce different types of Dreamlands.

Wondrous Vs. Mundane

Flowery descriptions of beautiful cities, enchanted sunsets and wondrous jewels are a core part of Dreamland. Of course, Lord Dunsany’s writing style easily lends itself to parody (as Ursula K. LeGuin put it: “a lot of made-up names, some vague descriptions of gorgeous cities and unmentionable dooms, and a great many sentences beginning with ‘And’”).

If you’re lucky and your players are good with wordplay, some Word uses might even be hilarious! It’s inevitable that a Dreamland game will have silly moments where the pseudo-fairytale speech patterns become self-referential. Since Dunsany himself occasionally made fun of his writing style in his later work, it’s natural if players do so as well.

If the DM wants to try to stick to the epic and poetic style of Lord Dunsany’s early writing, the best way to do this is to aim for this style in their own descriptions. There’s no right or wrong way for players to use Words. Roll with it, and try to steer things back towards Wonder afterwards if you like.

Scary vs. Safe

Dreamland can be a place of dangerously unstable reality, vicious killers and flesh-eating monsters. Abhumans and Nightmares embody horror, and the Pillar of Loathing provides a constant undercurrent of risk that violence or death might erupt into the game.

The overall level of horror in a Dreamland game is up to each individual group, but it’s safe to say that Dreamland is sometimes scary. “Sometimes scary” is perhaps a harder mood to pull off than “always scary”, since a given session may involve death, or may involve people transforming into abhumans, or may just involve fairytale themes, love stories and talking animals. Dreamland players must be prepared for the unexpected, though as with any roleplaying game, the DM should tailor material to the players’ tastes.

It’s difficult to imagine a completely nonviolent Dreamland due to the presence of Loathing Words, but a DM can choose to emphasize the horror and gore, or downplay it and have Words like “fear” and “blood” be mostly dramatic rhetorical flourishes.

Heavy vs. Light

The problems that dreamers face in the waking world, i.e., “real” problems, can be more difficult and depressing than blood-soaked fights with monsters. Lord Dunsany’s stories are often quite light (though some involve topics such as age and loss, the inevitability of death, or tragically doomed romance), but other portal fantasies grapple with heavy themes. In Pan’s Labyrinth the protagonist’s waking self deals with her abusive stepfather and the fascist government of 1940s Spain. In The Fall the protagonist is paralyzed and suicidal. Through the Garden Wall and Night on the Galactic Railroad deal with the death of a friend. In Lovecraft’s “Celephaïs” the protagonist sinks into depression and drug addiction before finally taking his own life. The beauty and fantasy of Dreamland is brighter in contrast to the misery of the waking world.

As with horror, the overall level of ‘heavy’ themes in a Dreamland game is up to each individual group. If players don’t want to tackle particular themes, the easiest way to ensure this is to discuss it out of character before the game, either in person or by email to the DM, who can then make a list of off-limit themes to share with the group without necessarily identifying who is uncomfortable with what.

Low-Tech vs. High-Tech

Dunsany and Lovecraft romanticized the past, so their visions of Dreamland are low-tech with no place for modern technology. For Dunsany especially, like J.R.R. Tolkien, the pre-industrial past was an idealized world of farms and pastures, a harmonious world of green nature, free of pollution, factory labor and other modern blights.

In the spirit of this, Dreamland by default is a fantasy mirror of the past. There’s no reason why technology can’t exist in Dreamland, but by default it’s rare. A low-tech, pseudohistorical feel doesn’t mean that Dreamland societies need to be regressive; firstly, it’s a fantasy, and secondly, going back in time can mean taking inspiration from matriarchal cultures and cultures with nonbinary gender, as much as from cultures of slavery and monarchy.

However, the average technology level of fantasy worlds has steadily crept up since Dunsany’s time, so players (and DMs) may enjoy playing in a world where things like airships and guns exist, and fantasy mixes with science fiction. The decision of how much high-tech stuff to put in the setting is entirely up to each individual campaign, and doesn’t affect the rules, as long as the magic that allows dreamers to travel to and from Dreamland remains mysterious and unquantifiable. Depending on how you and your players present them, such technological artifacts might seem rare and ominous, or absurd and intentionally incongruous, or as elegant and symbolic as everything else.

And of course, since player-generated marvels are by nature disruptive and can be drawn from the memories of their waking self, even if your version of Dreamland is classically low-tech it’s perfectly appropriate for players to use marvels to create things like cellphones and machine guns. As DM, let players create the marvels they want.

Remember also that one of the core elements of Dreamland—a sense of distance, travel and isolation—works equally well in an ancient or modern setting. Endless freeways stretching off to the horizon, lonely gas stations and rest stops, and endless rows of identical suburbs all fit perfectly into a Dreamland landscape.

Exotic vs. Familiar

To play a fantasy game set in an imaginary world unlike our own is to desire the exotic. The idea of Dreamland as an exotic place is a metaphor for the basic experience of roleplaying: in any RPG the players are privileged outsiders, in Dreamland this is worked into the rules.

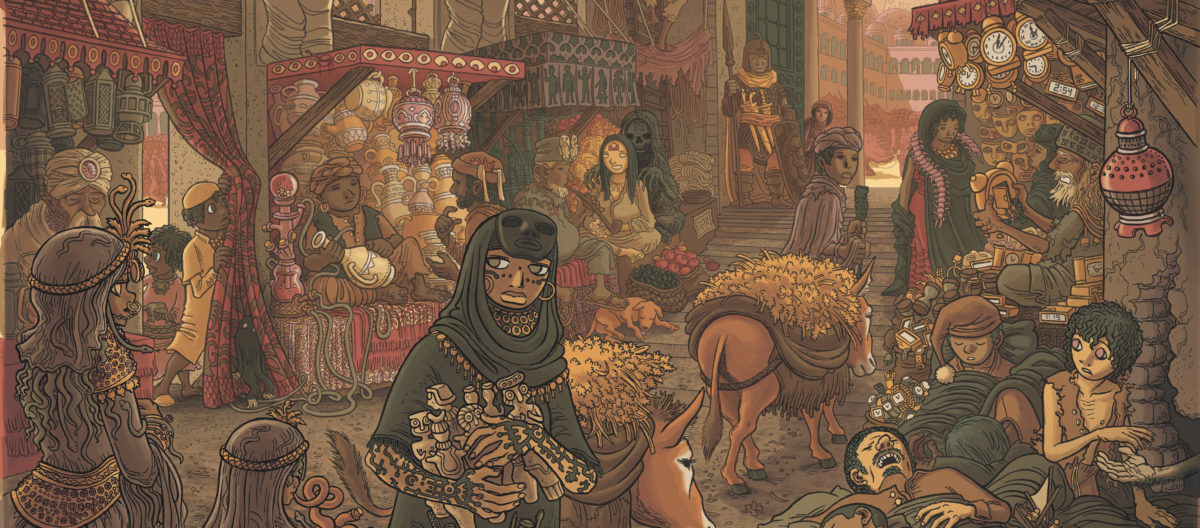

Travel narratives have inspired armchair explorers and dreamers from Herodotus to Ibn Battuta to Marco Polo to the 19th century Orientalists. The Orientalists of the Victorian era—wealthy Western explorers visiting the Middle East, Africa, and East Asia—definitely influenced the writing of Lord Dunsany and H.P. Lovecraft.

For many gamers this era of travel writing will have unpleasant connotations. (Indeed, the very word “exotic” isn’t something you want to call anybody in real life.) The Victorian Orientalists brought racist attitudes along with them and sometimes contributed to the military and colonial exploitation of the region, as described in Edward Said’s 1978 book Orientalism. Both Lovecraft’s and, to a lesser extent, Dunsany’s stories have racist elements.

But Dreamland the game doesn’t need to have an “Oriental” feeling. The cultures of Dreamland could follow in the pseudo-European style of Monty Python’s Jabberwocky, Brian Froud’s Labyrinth and Schuiten & Peeters’ Cities of the Fantastic series, or the pseudo-American fairytale style of The Wizard of Oz and Carl Sandberg’s Rutabaga Stories. A “jungle” could be a temperate rainforest or a tropical one, and a “temple” could be a pseudo-Christian cathedral or a pseudo-Asian pagoda. The “waking world” doesn’t need to be London or America. Dreamers’ waking selves can come from almost any time or place. As DM, you can describe Dreamland however you want it and define the “exotic” in whatever way works for you.

Isolated vs. Social

One of the core ideas of the philosophy called Gnosticism is that the “real” world we see is not actually real, and only a few people can achieve knowledge—gnosis—of true reality. This idea can be seen in the Matrix movies, in comics like Grant Morrison’s Doom Patrol and The Invisibles, in RPGs like Mage: The Ascension, and also in the world of Dreamland.

What makes Dreamland gnostic is not just that there is a secret world hidden beneath the waking world, but that the dreamers who know this truth are special people, alone out of the billions of humanity. Unlike in The Matrix, The Invisibles or Mage, there’s no secret organization which dreamers can join. Except for one another (and whatever rare dreamer NPCs the DM creates), dreamers are alone, and along with their power they face the constant danger of alienation, isolation and madness.

If this kind of lonely world of privileged, doomed outsiders doesn’t appeal to you or your gaming group, the easiest way to change it is to make some kind of superhero-esque NPC social organization of waking-world dreamers, like the Society of the Golden Dawn or the Medieval Italian benendanti, to provide community for the player characters. (Of course, an organized society of dreamers could potentially be more elitist than scattered dreamers, as the society uses its collective power for its own ends and draws lines between dreamers and mere ‘ordinary folk’.) Or, the DM could go further and emphasize that everyoneis on some level a dreamer, or has the potential of being a dreamer, even though most people are unaware of it. Such a democratized Dreamland would be a very different setting, and probably one with a higher level of magic and weirdness in the waking world overall.

These rules are intentionally ambiguous over whether non-dreamers also have “dream selves” and simply aren’t aware of them, or whether only the dreamers are truly alone with powers shared by only a rare few. This, too, is up to you to decide in your campaign.